By Polly Atwell

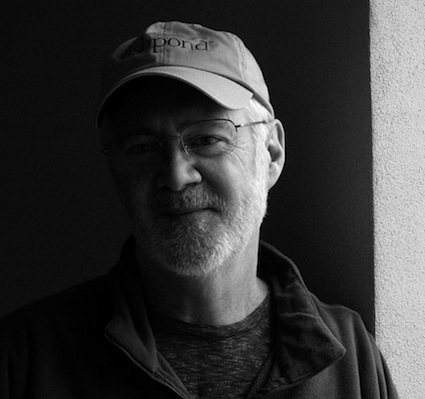

Mention

Jack Driscoll’s name to a fiction writer, and you’ll likely get nods of

recognition and admiration. Mention his name to someone who’s spent

time in northern Michigan and you’ll get the same response, perhaps with

even more enthusiasm. Since his debut story collection, Wanting Only to Be Heard,

was published in 1995, Driscoll has been recognized as the chronicler

of that snowbound and still-remote country between Detroit and the

Mackinac Bridge. His stories and novels mine the rural landscape,

producing characters that feel like people we know, whether or not we’ve

ever been north of Chicago. In his new collection, The World of a Few Minutes Ago,

Driscoll’s flawless sense of prose rhythm, his well-trained eye for the

perfect and often humorous detail, and his deep compassion for his

characters make the stories a great pleasure for writers and non-writers

alike.

Driscoll’s compassion and sense of humor extend into the

real world, where they have benefited legions of students at the

Interlochen Center for the Arts and the MFA program at Pacific

University. I was lucky enough to be one of those students, and

recently I had the chance to talk to Jack about his work, his life as a

writer and teacher, and what it means to tell stories of those small

rural communities at the 38th Parallel. An excerpt from our

conversation is included below.

“I’ve lived now for thirty-seven years up here in the northern

provinces, long enough to have witnessed a literal transformation of the

place itself. When I first arrived in 1975 there were, as I remember,

no full stoplights, and so at best we had to slow down a bit for those

blinking yellows, and the spaces between them mostly farmland and

uninhabited coastline. Somewhat barren but not as if ‘creation had

stopped halfway through the third day,’ to pilfer from Whitney Groves.

Because of the region’s great beauty, and the town’s gentrification, our

status as a destination—via the New York Times and elsewhere—has

coordinated an entirely new look. Coffee shops on every corner, and

upscale restaurants, film and literary festivals, organic co-ops and

farmers markets, and the population during the summer months increasing

tenfold. To varying degrees, cultural collision does occur, though

those inherent hostilities are not so directly confronted in my

stories. The focus for me is always something else, by which I mean

that tension created by what a place/community offers and what it can’t

possibly provide.

“Here’s our standing

joke: we have three seasons in northern Michigan—July, August, and

winter, and in 2010 we endured an official 209 inches of snow. Place

forms character. Or, as Ortega y Gasset says, ‘Tell me the place in

which you live and I will tell you who you are.’ Up north this

protracted winter season overlays and outlines a terrain as gorgeous as

it is terrifying, empty, cut-off, unforgiving. I’ve come to love such

extremes, and how these conditions conspire to define behavior. As the

teenage narrator in ‘That Story’ says, ‘I’m eye-level with the

snowdrifts that the wind has sculpted, the temperature single-digit at

best, and it’s beyond me why I say what I say, but I do, inviting

trouble of a magnitude that we don’t need and yet sometimes covet.’

Eliminate this frozen landscape and the story ceases to exist. It’s the

nature, I suppose, of a writer’s sensibility with a particular place,

where the characters’ inwardness is informed by all that surrounds them

in the actual physical world in which they operate. Nothing comes more

naturally—and less self-consciously—to me than setting my stories here,

where I’ve now lived for thirty-seven years. Not to mention the

wildness of such a terrain, which I’ve always, from the time I was a

little kid, craved, the woods and the waterways. And why writers such

as John Muir and Henry David Thoreau have been so important to me.”

This feature will continue in a second part, with a selection from “That Story” by Jack Driscoll.